A Brief Introduction:

2023 might very well be defined as the year of deepening nationalism around the world. We’re all keenly aware of the wars, soaring inflation, and regime shifts at the forefront of NYT and WSJ pages every single day. Yet I would argue that there is another deepening crisis that millions of people quietly suffered through this year. One that particularly impacts cisgender women: infertility. Most of us have seen the statistics, such as how the US fertility rate reached an all-time low of 1.6% in 2020, and how ART cycles have reached an all time high. But what if we double-clicked a few layers deeper? Why is fertility declining? Why do less than 15% of women receive treatment for postpartum depression? Can technology help diagnose conditions like PCOS even earlier? Below, Alliyah E. Gary (Harvard MBA Candidate ‘24), masterfully attempts to answer some of these difficult questions in Part I of this series on the deepening fertility crisis.

-Megan

______________________

The following features a guest post written by Alliyah E. Gary (Harvard MBA Candidate ‘24)

Setting the Stage: Defining Women’s Health

Women’s Health, sometimes more affectionately coined Femtech, focuses on technology companies that improve the health and wellness of women by addressing conditions that solely, disproportionately, or differently affect them. Women’s Health can be grouped into 4 main categories aligned across a woman’s lifecycle and continuum of care:

Despite the more than 160M women living in the US today, Women’s Health had chronically been under-researched and siloed for over a century, until 2022 when investments reached an all-time high of $3.3B. Exits also peaked, with nearly 50% of all Women’s Health exits occurring in the last five years.

Women’s Healthcare Services in the US - deal size by provider segment ($B)

Source: Investing in the Next Generation of Women’s Health. BCG. July 2023.

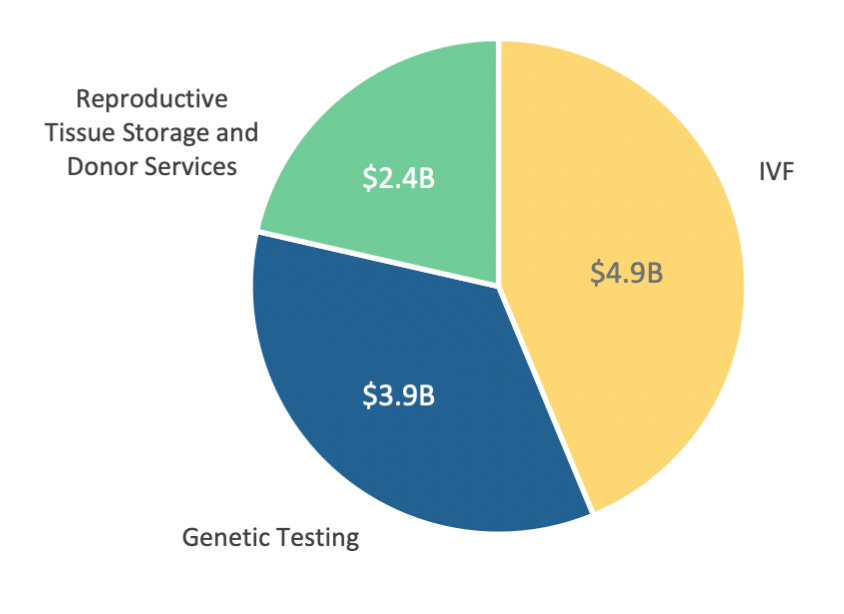

Fertility and pregnancy are virtually recession proof, so perhaps it is no surprise these subcategories have received the most attention, accounting for over half of the investment dollars in women’s health in 2022. After all, unborn babies are unaware of pandemics, wars, and market volatility. As of 2023, the U.S. fertility market is worth ~$10B, with IVF representing nearly half of the market and poised to grow at a 12% CAGR through 2025.

2023 US Fertility Service Market ($B)

Source: Fertility Market Overview. Harris Williams. Q3 2023.

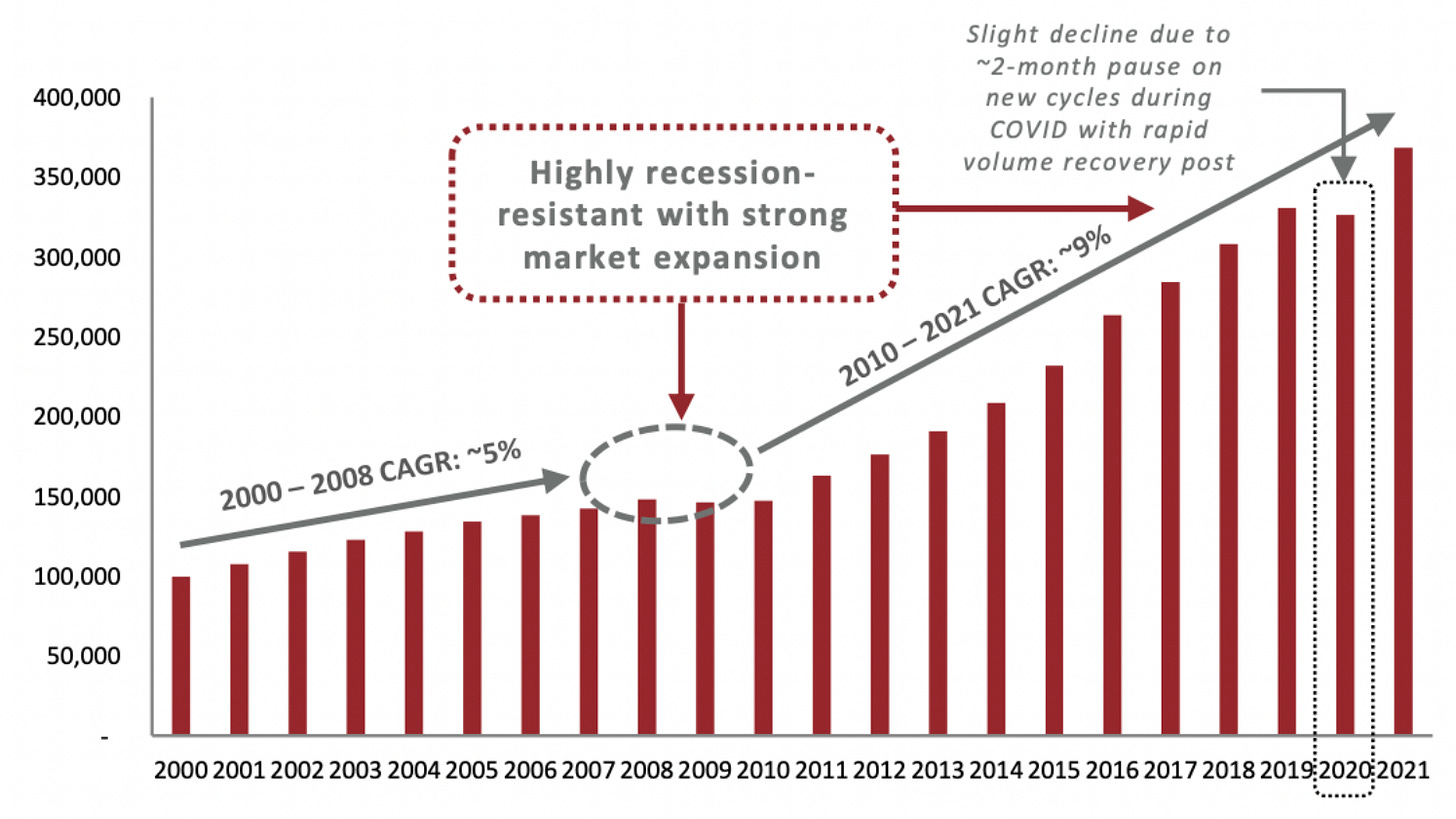

Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART) Cycles Performed in the US

Source: Fertility Market Overview. Harris Williams. Q3 2023.

Investing in Fertility: Why this is just the beginning

Now that we’ve set the stage on women’s health, let’s dive into the largest and perhaps most defining category over the next decade: fertility.

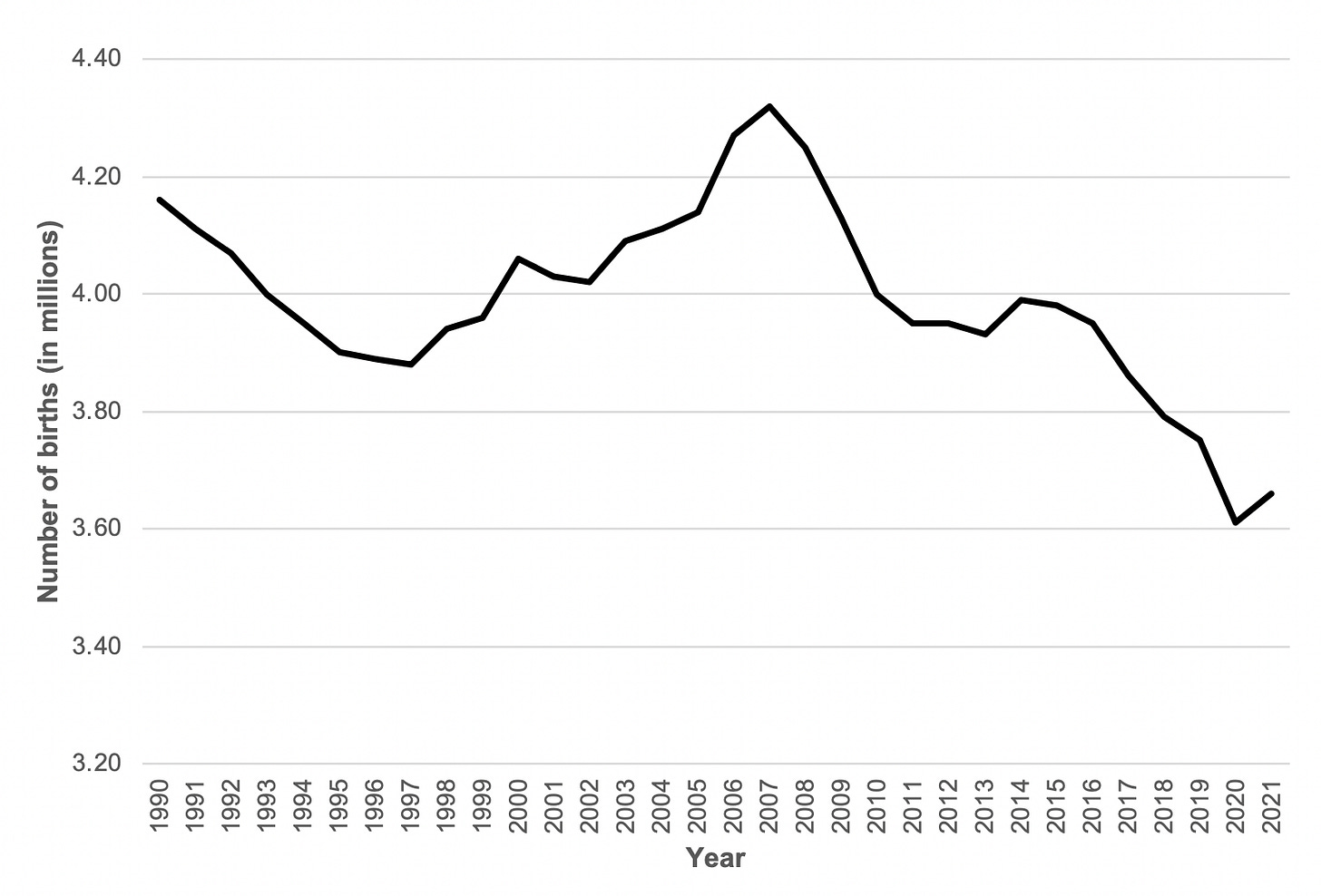

Fertility is in a state of crisis. According to the World Health Organization, approximately 48M couples and 186M individuals live with infertility globally, defined by the failure to achieve a pregnancy after 12 months or more of regularly trying. Fertility has decreased by ~40% over the past 50 years, with Canada’s decline being the highest at 62%. In the US, fertility has declined by over 50% to an all-time low of 1.6% in 2020. This now puts the US below the average replacement level of 2.1 children per woman.

Births in the United States from 1990 - 2021 (in millions)

Source: National Vitals Statistics Report. CDC. January 2023.

Total Fertility Rate in the United States from 2006 - 2018

The Total Fertility Rate Reached an All-Time Low of 1.6% in 2020

Source: Measuring Fertility in the United States. University of Pennsylvania. July 2022.

The Cause of Declining Fertility

There’s been a cultural shift of women prioritizing education and careers and, as such, often choosing to start families later in life. This has caused a steep decline in fertility for women in their 20s, arguably the most ideal biological time to have children, accompanied by an increase in women giving birth in their 30s and 40s. This tradeoff, however, comes with a natural decline in women’s ability to conceive associated with increased complications.

Age-Specific Fertility Rates Over Time from 2006 - 2019

Source: Measuring Fertility in the United States. University of Pennsylvania. July 2022.

With age, chronic conditions begin to gravely impact fertility for both men and women. Today one in five pregnant women suffer from at least one chronic disease and globally chronic conditions are on the rise, increasing ~14% annually. Hypogonadism (also known as low testosterone), erectile dysfunction, celiac disease, and testicular and post-testicular deficiencies are common chronic conditions impacting male fertility; while uterine fibroids, endometriosis, and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) are some of the most common chronic conditions contributing to a decline in female fertility.

Although awareness of these chronic conditions are on the rise, diagnosis still remains challenging for women. Let’s take endometriosis as an example. On average, it takes ten years to be diagnosed as many don’t know to seek care. Women often mistake endometriosis symptoms – painful periods, intercourse and excessive bleeding – as ‘normal.’ My friend made this all too common mistake. For years she dealt with compounding symptoms and, when she eventually sought treatment, healthcare professionals misdiagnosed and dismissed her, as her lesions were not detected on ultrasounds. Only after additional research of her own and consulting yet another gynecologist was she properly diagnosed; at which point her chances at naturally conceiving had declined drastically. “The chance of getting pregnant each month for people with surgically documented endometriosis is only 1-10%."

This news was devastating for her; though many women don’t discover they have endometriosis until it's too late, if at all – six out of every 10 cases of endometriosis remain undiagnosed. The good news is, with early stage diagnosis (stages I or II), treatment is possible and pregnancy rates increase significantly. After laparoscopic surgery, 93% of patients experienced relief from symptoms and over 65% of patients were able to conceive – many of these pregnancies occurring naturally. Ultimately, the market knows how to solve this problem, we now need increased investment and continued awareness to do so.

I firmly believe that where capital and resources are deployed is precisely where real change and impact will take place. This continues to reign true, even for the most complex problems, such as climate change – a much less talked about factor contributing to infertility today. A recent study conducted by the NIH found that a 1°C increase in summer temperatures led to 1% or more fewer births nine months later in many U.S. states. High temperatures affect our body’s natural ability to regulate temperature and pregnant people – whose body temperatures already average higher than usual – are particularly vulnerable, experiencing adverse maternal and fetal health outcomes as a result. Studies show maternal heat exposure heightened the risk of preterm term birth by ~16%, decreased birth weight, and increased stillbirth and harmful newborn stress.

Aside from direct fertility implications, climate change exacerbates social determinants of health, including long-term disruption of housing, food insecurity, and economic conditions, which widen the fertility gap. People in developing countries, such as India and parts of Africa, as well as marginalized communities are at greatest risk.

These risks are exacerbated by modernization and technological advancements. Many aspects of our lives today directly contribute to the decline in fertility – in both women and men – including an increased exposure to harmful chemicals, sedentary lifestyles linked to rising obesity and other physical and psychological stressors.

Ultimately, conception does not occur in a vacuum. Where we live, what we eat, the lives we lead, and other factors outside of our control have a direct impact on fertility.

Beyond Conception: Addressing Disparities in Maternal & Infant Outcomes for Marginalized Communities

For those who can conceive, mortality rates are much higher in the US than other developed countries. Nearly a thousand women die annually because of pregnancy or related complications with 84% of these deaths deemed preventable. The most common health-related causes are cardiovascular conditions and mental health – underscoring the importance of addressing chronic conditions and leading a healthy lifestyle, both physically and mentally.

And it’s no secret that huge maternal and infant health disparities exist across races and ethnicities. Black women are three times more likely to die from pregnancy-related complications than white women, widening to over four times as maternal age increases beyond 30. Moreover, children born to Black women experience mortality twice as often compared to white children and have an increased risk of preterm birth and low birth weights. Marginalized communities as a whole are more likely to receive late to no prenatal care and experience other life-threatening complications as a result, such as preeclampsia, blood clots, and postpartum hemorrhage.

Deaths per 100,000 live births

Source: From Birth to Death. AP News. May 2023.

The overwhelming disparities in maternal and infant health are driven by the structural and systemic racism underpinning our society. Controlling for other socioeconomic factors, such as education, income, and employment, disparities in communities of color still persist. Black mothers are less likely to be believed and treated for pain and more likely to be tested for drug use, although more white mothers test positive for drugs.

Sadly, the discrimination inherent in our healthcare system is due to a gross underrepresentation of people of color in medicine. In 1910, the Flexner Report which aimed to create common standards and curriculum across medical schools in the US simultaneously resulted in the closure of 82 schools nationwide, leaving only two Black medical schools remaining. Over a century later, the impact can still be felt today. Only 10.7% of active and practicing OBGYNs in the US are Black and over 80% of them are trained at the only Black medical schools in the nation – Howard University and Meharry Medical College. Consequently, there is a lack of culturally sensitive care for communities of color, exasperating maternal health disparities.

Access to care and insurance coverage for people of color also pales in comparison to that of their white counterparts. The US is one of the few developed countries that does not have a national policy ensuring paid leave for new parents and women of color are less likely to have access to paid leave through work. Moreover, marginalized communities are more likely to encounter barriers in accessing care and far more likely to have inadequate or no insurance coverage at all. 65% of Black mothers rely on Medicaid – compared to 42% of all other US mothers – which only provides postpartum care for up to 60 days, while more than a third of maternal deaths occur one week to a year postpartum. Meaning most Black mothers lack adequate coverage to seek the care they need postpartum and often return to work too soon. The consequences of these care gaps are immense and too often fatal for mothers of color.

Pregnancy-Related Mortality (per 100,000 births) by Race/Ethnicity from 2016 - 2018

Source: Racial Disparities in Maternal and Infant Health. KFF. November 2022.

While the mortality rate for Hispanic women is the lowest amongst all demographics in the US, the fertility gap has widened the most for Hispanic women. From 2006 to 2017, their fertility rate dropped 31%, compared to 5% and 11% for white and Black women respectively. This is an abrupt shift from the last decade when Latinos were key to the US’ growing population, producing more children per woman than any other demographic. This change is driven primarily by women of Mexican heritage, whose fertility rate declined 37% in that period. Underpinning the decline is an increase in the number of American-born Hispanics, who are more educated and aligned with the US cultural attitude favoring delayed family planning, compared to the norms of their less-educated immigrant mothers and grandmothers. Now, more Hispanic women are having children later in life and here in the US where they are more susceptible to the racial and structural biases pervasive throughout the American healthcare system.

Where do we go from here?

While increased research, investment, and awareness in the private sector have been instrumental in driving change in the fertility space, public policy in the US lags behind and still has a ways to go. To fully address these challenges, it’s going to take the support of both the private and public sector. Despite the challenges, I believe there is hope.

Last month, the White House announced the first initiative for women’s health research, led by Jill Biden. In this landmark decision, various federal and executive agencies will work alongside the private sector to provide the Biden administration recommendations on how to close the research gap for women’s health through diagnosis, treatment, and prevention plans.

“It’s a big day for every woman in this country, no matter her age, her political affiliation, her religious identity or ethnicity. This is a historic moment for women and their families and their health care providers.” - Maria Shriver

Change is on the horizon! Which side of history will you stand on?

_____________________________

1 Harbin Clinic. (2022, July 20). Female Life Stages - Harbin Clinic.

2 Understanding Fertility: The Basics. (n.d.). HHS Office of Population Affairs.

3 Role of Canada in Global Health Sector – Main Takeaways. (2023, July 3). CCGH – Canadian Conferences on Global Health.

4 Wright-Mendoza, J. (2019). The 1910 report that disadvantaged minority doctors. JSTOR Daily.

5 Farr, C., & Schrock, L. (2023, June 7). Why the fertility market is poised to explode. Second Opinion.

6 Borght, M. V., & Wyns, C. (2018). Fertility and infertility: Definition and epidemiology. Clinical Biochemistry, 62, 2–10.

7 Fewer Latino births, more deaths have an impact on nation’s slower growth. (2021, December 22). NBC News.

8 How Chronic Conditions Can Affect Fertility. (2022, August 2). HealthCentral.

9 Chen, M., Haq, S. M. A., Ahmed, K. J., Hussain, A. H. M. B., & Ahmed, M. (n.d.). The link between climate change, food security and fertility: The case of Bangladesh. PLOS ONE, 16(10), e0258196.

10 How can we solve the Black maternal health crisis? (2023, June 27). Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

11 How climate change is likely to worsen reproductive health for generations. (2022, October 4). University at Buffalo.

12 Greub, E. E. a. L., & Greub, E. E. a. L. (2023, January 19). The rise of interest & investment in women’s health. MedCity News.

13 The shifting conversation around investment in women’s health care - Insights - Proskauer Rose LLP. (n.d.). Proskauer.

14 Improving health for women by better supporting them through pregnancy and beyond. (2019). Commonwealth Fund.

15 Healthcare Investments and Exits. (n.d.). Silicon Valley Bank.